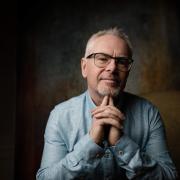

Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen is marking his 60th year by going back to the easel - with his first ever fully curated solo show, Gardens of Baroque Delights. Katie Jarvis attempts to paint a picture of one of the nation’s best-loved celebs

Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen and I are reminiscing.

A pleasurable as well as baffling pursuit.

‘Mobile phones,’ I say, in the same voice I’d use if Facebook called to ask me to design an algorithm.

‘I was having a conversation with my daughters,’ Laurence pitches in, ‘about when Jackie and I first started going out in 1985. She was living in Paris and I was at Camberwell art school. They asked me, ‘But how did you communicate without mobile phones?’’

We both shake our heads. Ah, the arcaneness (is this a word? A side-effect of being with Laurence is a desire to make up words) of modern life; our bodies present, our brains puffing at some distance, yelling, ‘Wait for me.’

Actually, Laurence adds – as if Facebook has now asked us to throw in biometrics – ‘We didn’t have telephones!’ Nobody could afford one. We wrote letters, sometimes twice a day.’

And the joy of getting a letter!

‘Oh, my god! It was incredible.’

Double whammy, though. Not only is the present indecipherable; the past is pretty bemusing, too. How did we manage in our own Stone Age?

‘How did we know where people were? Jackie had an incredible social life in Paris. We must have all decided we would meet at a certain place at a certain time.

‘If Jackie and I wanted to speak, we would write a letter and say, “Can you be near a telephone at 6 o’clock on Friday and I will ring you!” That sounds so exceptionally quaint.’

Maybe, we muse, if - from teenager on – we’d stuck to plant-based diets, put ourselves to bed by 8pm with a mug of 85 percent organic cocoa, and concentrated on achieving Enlightenment through non-chemical means, we’d all be down with the kids now. What fools we were.

‘We were all, “Blah, blah blah.” The problem is, most of us thought we’d be dead by 23 so we didn’t really know how to do the rest of it. The big thing is that you spend more of your life old than you do young - so you’ve got to be very good at being old.’

We sit for a moment, gazing into mid-distance.

But Laurence has an ace up his sleeve.

I’M HIGH UP in an office above the Llewelyn-Bowen design shop in Cirencester, staring into the depths of Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen’s soul.

I’ve never doubted it’s a beautiful soul.

But here is 3-D proof of that conjecture.

To my left is a series of canvasses, casually displayed.

‘First time they’ve been all together,’ Laurence says, nodding at them. ‘They’re being picked up tomorrow.’

I mean, don’t rely on my amateur attempts at description; look at them for yourselves. They are stunning in their gorgeousness. Like a dream. Deep, sensuous colours; exotic animals – leopard, peacock, flamingo; fantasy unworldliness.

‘Jackie said, “Oh, my god! They’re so Cecil B DeMille.” And it’s like, “Oh, my gosh! You’re so right.” They’re little filmsets; they’re stills. They’re so evocative you think there’s a narrative; there’s something about to happen; something just happened.’

Exactly. But are they utopian or dystopian?

Would I like to wander through these fantasy-scapes, dipping my fingers in ice-cold cascading water, leaning against the cool of stone columns, dazzled by the colours and spicy scents of a hot clime? Or should I be afraid? Very afraid.

‘I love all of that. Who says what’s white; what’s black; what’s good; what’s bad. Particularly in nature: you can have a pair of leopards - and they’re things of great beauty - but they’ll rip your face off.’

Who built the temples in these canvases you can step into? And why?

Full-colour Piranesi.

‘He was bat-shit crazy.’

Laurence might be of an age (he’s not old, for goodness’ sake; these are his words, not mine) where his PIN and mobile phone numbers are like dandelion seeds on the breeze (‘And I don’t say that with pride because I think that sounds a bit arsy and a bit irritating’) (besides which, that’s a conceit, not an age-thing. He can recite the mistresses of the various Louis, Kings of France, or facts about the Renaissance with the ease of a 12-year-old listing locations in Fortnite) (too many brackets; apologies), but he’s entering a new phase with teen enthusiasm.

He’s a classically-trained fine artist – don’t for a moment doubt that. But his years of TV celebritay (his pronunciation) stopped his painting pretty much in its tracks:

‘…when I was 22. And all those years of Jackie being so regretful – ‘Oh, you smelt of linseed oil, and it was so sexy when you were a painter. Now you’re just an orange celebrity.’ All of this stuff.

‘To suddenly say: Actually you can; and do it large.’

And with consummate skill. These are beautifully, beautifully executed.

‘It’s well-worn territory [turning to art]. Bob Dylan. What’s he called from the Rolling Stones? Bill Wyman. Johnny Depp. And they’re what you expect: a bit album covery; a bit splodgy; drawing’s not quite there.’

These are so not so.

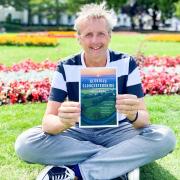

Named Gardens of Baroque Delights (each with their own ‘garden’ moniker), they are sumptuous in their mastery.

‘I’m very keen on the skill side of it. I spend an enormous amount of time polishing up my skills as an interior designer; as a television presenter.

‘These aren’t trophy pieces of art. The “I’ve got a Bob Dylan” or – dare I say it – “a Rolf Harris.” These I’m hoping are going to be loved for what they are… brackets by Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen.’

We sit for a moment, gazing into mid-distance. Me, thinking thoughts on psychology; Laurence, who knows.

THE THING IS THIS, I say to Laurence.

We’ve never really talked about ‘you’ you before. Yes, yes: we’ve talked about his home in Siddington (which he took to like a duck to the Cotswold Water Park); about his charity work (he and Jackie are quietly amazing); about TV makeover participants who failed to share quite his relish for redecorating their homes in 23 shades of brown.

But we’ve never really discussed his background.

Looking at these ‘Baroque’ paintings – all drawn from his mind – it’s set me wondering who he really is.

Here was a child of an eminent, high-achieving dad. A Harley Street surgeon, who died of leukaemia at the age of 42, when Laurence – the eldest of three - was aged just nine.

‘I was thinking about that baggage,’ I say to him… ’sorry; not a great choice of word…’

‘It’s a good enough word for it.’

‘Of having a high-achieving dad; and then that very formal relationship with your parents [as he has described it]; and losing him when you’d never got to know him. Those teenage years without that: This is who I am; or This is who I reject.’

‘I was quite lucky because I was growing up at a time when that wasn’t pre-supposed to be a big problem. Actually in the 60s, 70s, it’s before child psychology takes over and tells you that your father dying and your mother being very ill is going to be a negative.’

Ah, yes – I hadn’t even factored that in, to my shame. For his mum was diagnosed with MS at a similar time to his dad dying.

‘I do genuinely feel that my childhood was a state of neutrality rather than a state of tragedy, for sure. Children are very good at just being able to cope.’

Sure. But the difficulty can come later, looking back.

‘Yeah… People have troubled childhoods when they’re adults. Children don’t go to doctors and say, “I’m in the middle of a troubled childhood.” And certainly I don’t feel like that.

‘I was frogmarched to a child psychologist when I hit teenagedom. I remember enduring it for several months and then thinking, “This really isn’t helping; I don’t see where this is going; what it’s giving me. I’d much rather be getting on with what I need to get on with.” And that’s something I’ve very much inherited from my mother.’

His mother, clearly, was an incredibly strong influence.

A feminine voice?

‘That’s interesting. ‘Feminine.’ Is that the right word? Very matronly… Very matriarchal. There you go – that’s the word.’

Can he give me a memory of his dad?

‘No – genuinely. No. Because everything I can remember will also have a photograph attached to it. So I think you manipulate your past.’

His mother – he can now see – very much struggled after his dad died.

‘But it manifested into terrible crossness about it. Very pissed off with him. Also, I think if you’re a very strong person, that’s the way you go. There was nothing maudlin about her. I saw her cry about twice, and she was incredibly embarrassed. We were…’ He mimes the children’s (as I interpret it) utter bewilderment and horror.

My questions are leading up to whether or not his father’s job – and his death – influenced Laurence’s decision to train as an artist.

But I don’t even need to ask.

‘Yes – if a mid-Victorian novelist was writing it: If my father had lived, he would have been very disapproving of me rushing off and becoming bohemian. But, actually, he was quite creative himself. My mother used to say that he felt he’d been rather frogmarched into studying medicine and would have wanted to do something very creative.’

His dad made dolls’ houses, a train for his sister. He was obsessed with heraldry. Came from a creative background.

‘In hindsight, he was a very expansive character. I think calling him ‘flamboyant’ is going too far. (I’m having that word. That’s mine, not my father’s.)

‘He was very telly friendly. He was on telly a lot. He was quite good-looking and he looked quite dashy.’

And then he gives me a memory.

A very interesting memory.

I’m not going to play amateur psychologist.

But a very interestingly framed memory.

‘One of the big things was always Christmas Day, live from the children’s ward. It always seemed to be his children’s ward. I remember my mother being quite snippy about the fact that all his female patients – whenever he did a ward-round – made sure they’d had their hair done; and they were sitting there in their best negligée.

‘One of the few memories I do have is not actually of him but of being part of his flotilla during a ward round. I remember with such clarity this large cast of backing singers: ‘Carry On nurses’ nurses who, in those days, had these enormous starched wimples, which I remember bounced up and down like gulls when they walked. Their incredibly shiny black stockings. I think this is awful and immoral, obviously, objectifying these poor hard-working nurses. I do remember the visual impact of him at the epicentre of that V, walking like a flock through these big Victorian wards.

‘And I can remember everybody sitting up and paying attention.

‘I can remember his importance.’

THERE’S TOO MUCH TO SAY in one article.

I haven’t even mentioned the stop-press. That he’s handing over the reins of the interior design business to his daughter, Hermione (‘She’s doing the most amazing things with it’); his son-in-law, Dan, is focusing on the licensing.

And Laurence?

He’ll be painting, of course. Another exhibition, probably in 18 months or so. And commissions – of houses. He shows me one of a home in Minchinhampton: strange and wonderful. The property is depicted with elegant exactitude; the surroundings are from his mind.

‘It is [a painting of] when you dream of your home when you’re away, which I’ve done a lot of. Your vision is very gilded and golden; it’s an ideal; it’s an avatar.

‘All of us, we’re obsessed by our houses; our houses are refuges after Covid; after all the stuff that’s going on at the moment – geopolitics; economics.

‘So why not make it the fantasy house you’ve always wanted it to be.’

Sure.

But now here’s my last question. The one I’d really like to ask.

Might I bring his dad back? What would he put him in front of to say: ‘This is me. Be proud of me, dad’?

Not a hesitation.

‘My wife. He would have adored her and she would have adored him. They were a match made in heaven.’

We sit for a moment, gazing into mid-distance. Him thinking – almost certainly – about his beloved family of today. Me thinking, we haven’t even mentioned Changing Rooms.