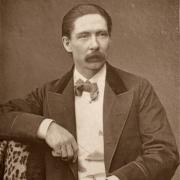

Katie Jarvis talks to Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones MBE to learn how a child of the Windrush was able to move from an inner-city Birmingham terrace to owning a farm and hugely successful business

So, get this.

I email press@theblackfarmer.com out of the blue, kindly to request – more in hope than expectation – an interview with the ‘Black Farmer’ himself, Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones.

(You know. The Black farmer who came from less-than-nothing; who grew up in a tiny, bursting terrace in Birmingham with eight brothers and sisters. Whose sausage brand is in every self-respecting supermarket in the land.

The Black farmer who can stand at his farmhouse door and gaze, eye roving over field and hillock, at the swathe of land he now owns.

Yes, that one.)

(Look. I genuinely understand that you don’t need my angst about the traumas and hurdles, blah, blah, blah, of trying to track down interesting interviewees for you. But, honestly, these requests end up in machines longer than an industrial sausage production line.)

So I hit ‘send’ and watch my email fly off into ‘We’ll let you know’ cyberspace, and prepare to age while awaiting an answer.

And, then:

Ping.

Thanks for this Katie. I would love to be interviewed. Will you be able to call me on Thursday 3.30pm that will be a good time for an interview because I will be travelling back to London so I have got time on my hands.

Blimey.

Blimey in a really, really good way.

IT’S STRANGE, I say to Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones.

(NB: After: ‘I can’t believe you replied so quickly. What a nice man!’)

Strange that a child whose life was pretty much defined by food poverty – one puny chicken to feed a hungry family of 11 – should retain such seemingly happy memories of food. Shopping with his mum – a factory worker – at Caribbean markets outside the Bull Ring, Birmingham. Markets where you’d hand your hard-earned cash to the stallholder, and he’d give you in return a chicken with all guts intact.

Ah, yes, Wilfred remembers. Every Saturday morning.

‘What was brilliant about that outdoor market was that it was full of theatre – all of the people who used to shop at those markets would get their weekly fix of entertainment. The guys were brilliant salesmen – they knew how to charm the ladies.’

I mean, sure.

But those charmed ladies were canny, too.

‘The whole ritual of inspecting food… The idea that you would just pick something up and put it into the basket did not exist.

‘They even used to sell hens you’d have to de-feather – that would be even cheaper.’

Not nowadays, though. Health and safety gone mad.

‘Cooking was a whole day at the least - sometimes a couple of days. Those chickens would be pot-roasted, meaning you’d have to cook it slowly with not much liquid. But that needs a lot of attendance; you’ve got to make sure the water doesn’t run out or the whole thing burns.’

You can’t just pop out and grab another.

‘Exactly.’

I can practically hear him smacking his lips.

‘The heart and liver. The liver was like a little treat; you’d fry it because that doesn’t take much cooking, and then you’d have that as a tiny snack.

‘The neck would be pot-roasted as well; being able to get all that lovely tasty flesh from the chicken neck – these were elements you don’t really get any longer when you buy a chicken.

‘That was what was absolutely gorgeous about eating chicken in those days…’

I’VE TRIED GOOGLING what the Black Farmer brand is worth. (Seems rude, but there you go.) Truth is, I’m baffled by figures: I can only tell you ‘Millions’.

But that’s not really the point.

The value to so many is way beyond pounds, old shillings and new pence.

It’s that a Black man, child of the Windrush generation, made it big. And then, instead of slipping invisibly into the multi-cultured richness of city life, he moved into an English countryside that had barely seen other than a white face, or heard a name that wasn’t pronounced with charming burr. A place that still thought it was OK to talk about ‘coloured people’. A countryside about which, one friend asked, ‘Don’t they lynch people like you down there?’ (Even that’s rephrased. The friend didn’t actually use the words, ‘people like you’.)

And, of course: we’ll talk about the fact that Wilfred is now an independent governor of Cirencester’s Royal Agricultural University.

But this is a story (trust me) where you need to start back in the late 1950s – Teddy Boy quiffs and drainpipe trousers; but also landlords who felt it was fine to put out signs reading, No blacks, no dogs, no Irish – to get a true sense of it. That was the era when two young people travelled from their native Jamaica to a rainy England, leaving behind two children in the care of extended family.

‘Imagine that!’ I say to Wilfred. Imagine your parents having to wave goodbye to two babies; to you and your older sister.

He shakes his head. It wasn’t an aspect of life he ever really thought about until he had his own children.

‘And that’s when you realise what a profound experience that would have been...

‘I can always remember, when I had my first child, how much they know at the age of three months. So the idea that, as a child…’

He tails off momentarily.

‘And then to have been brought up by my aunt, who I would have seen as my number one carer. And then to come to the country [England] and be brought up with strangers…’ Those ‘strangers’, of course, being his parents, whom he and his sister joined when he was four.

Yet. Before we let that percolate, let’s throw into the mix the bitter reality of economic migration.

‘It was really tough and difficult for my parents [coming to the UK]; but even so, it was better than the options back in Jamaica. Sometimes we romanticise what it was like to be brought up in that environment. My mum used to tell me how she’d have to walk miles to school. Before she went to school in the mornings, she had to go and fetch water. No electricity supply. It was really, really poor.

‘So, as difficult as it may have been in this country, it was still better than being back in Jamaica, being brought up in absolute poverty.’

As difficult as it may have been…

Eleven of them – his parents went on to have seven more children – squashed like the sardines they couldn’t afford into a tiny terrace in Small Heath, Birmingham.

There’s a scene in his book – Jeopardy (a sort of self-help/motivational/business-success book) – in which he revisits his home area 30 years after he’d left. It’s for a television programme being made about him.

‘Then, I was a poor, dyslexic, Black youngster in a Britain where racism and intolerance were still the norm. Now, returning with a television crew in tow, I am an entrepreneur and a land owner – and someone wants to turn my story into a documentary.’

It’s not the two-up, two-down he writes about on that visit.

It’s the nearby allotment, at Yardley Wood, rented by his dad to supplement the sparse family diet. Wilfred stands looking at the ruins of the shed he and his dad built together. Moss has commandeered the asphalt roof; the door (still with a smattering of familiar blue paint) is lying on the ground. ‘It looked like the worst-kept garden shed in the world. Still, to me it represented everything.’

It was standing amongst these vegetables – as close to a feeling of space 10-year-old Wilfred would ever find in inner-city Birmingham – that he made a promise to himself. One day, he would own a farm…

His parents thought he’d gone mad.

‘Their attitude was: If you get a job working in the local factory paying x amount, just be grateful. The idea that you are thinking about farms - that belongs to the loony bin.’

That 10-year-old didn’t get his farm through academic success, parental contacts or Oxbridge knowhow. He got it by setting crazy goals and doggedly persevering until he met them. For a whole year, he hung out by the BBC studios, volunteering to help security guards and cleaners until he secured a job as a general runner. Then followed a 15-year career in television during which he travelled the world making food programmes.

SO, WHAT WOULD that 10-year-old boy think of the world today?

Not just of his own success. But of a world where America has had its first Black president. Where Britain has its first Prime Minister of colour?

‘The reason we had Barack Obama is decades of Black consciousness in America; Blacks becoming a lot more political; becoming very much part of the mainstream.

‘The Black experience in the UK is very, very different. Achieving things is not necessarily down to your ability but what background and class you’re from. That has actually held back the progress of Black people in the UK.’

In the 2010 general election, he stood (unsuccessfully) for the Conservative Party in Chippenham.

For him, the political left just doesn’t cut it.

‘People like Diane Abbott… The left really comes from a victimhood. It’s all based on how badly treated we’ve been and how white people need to apologise for that and give us a break.

‘Now I am really with the politics of the American Blacks. We should not be spending our lives asking for permission. Just go out and create it.’

So, is the current Tory immigration policy right?

‘Are we talking about illegal or immigrants coming in from abroad?’

(Interestingly phrased.) The choice is his.

‘One of the things Brexit taught us is, any country that feels as though immigration is happening at such a fast rate that the host community are feeling as though they’re missing out, is dangerous.’

Reliance on cheap labour is a problem, too, he says.

‘The war in Ukraine has taught us that, if we become reliant on things outside of our country, that’s a dangerous place to be. We need to motivate people in this country to do the jobs we’ve tended to rely on immigrants to do.’

SO, JOINING THE Royal Agricultural University. I mean, bravo to both parties.

But it made me double-take. Surely, historically, this is an institution that represented so much of what Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones has been fighting to change?

The perception of rich, posh kids who’ve always been in farming.

‘The reason I was keen to be a governor is because of exactly what you have just said.

‘I’ve got to give them credit for taking me on – because I’ve always said that anyone who takes me on knows it’s not a person who’ll stand by and watch the status quo.

‘I’m there to start thinking about what we can do to bring about change.’

Such as?

‘It might be something as simple as a job advert – rather than advertising in Farmers’ Weekly. How are you going to get diversity if you’re not reaching out to them in their environment?

‘Even things like giving out honorary degrees. Why can’t it be a black person?

Challenging the way things have always been done. If you’re not there, you can’t challenge it.’

Big estate owners – including the National Trust, English Heritage, the Church of England – should be held to account in terms of renting out property to people from diverse backgrounds.

‘We need a system that brings new blood into farming. The reality is that, if you’re from a non-traditional farming background, the chances of you getting land are almost impossible. I’m not advocating that private farmers should give their land away; but a lot of the big institutions own most of the land in this country. They could be saying to their land agents: ‘Go and find new entrants to rent the land!’

‘Look at some of the most vibrant, interesting industries – say catering. All the celebrity chefs; new ideas; new thinking: that makes it a fantastic industry to be in.

Farming is the same old stuff – no new thinking. Yet that’s what we desperately need.’

HE’S AHEAD OF the game himself.

Big fan of Morris dancing. ‘Part of what I love is eccentricity. You get ordinary people who dress up in this crazy gear, going out and having this amazing little dance.’

Adores Flamenco. ‘Raw passion; if you are prepared to give your soul to your art, it really stirs you.’

And is about to open the first ever farm shop in Brixton this October.

‘The idea is to take the farm-shop experience to towns and cities, because the only place you can really get a farm shop experience is in rural Britain. So, I’m opening my first for Black History month.’

Taking the countryside to the city. Yep – great move.

But the move has to be in both directions.

‘Change ain’t going to happen unless more Black people have the courage to go into rural Britain and claim their space there.’

• The Black Farmer is at theblackfarmer.com

• For more on Cirencester Royal Agricultural University, visit rau.ac.uk

• October is Black History Month. Visit blackhistorymonth.org.uk