Tweedy the clown and Jeremy Stockwell are appearing in the Shakespearean great A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but with Zoom failures and persistent talk of bottoms, the interview turns into more of a Comedy of Errors

So. Tweedy the clown and Jeremy Stockwell are about to star in Cheltenham Everyman’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream… (Did you see them together in the Everyman’s Waiting for Godot?? A production where – for once – you could completely understand why Godot bailed and went down the pub instead. Would have been totally upstaged.)

‘Would you like to interview them on Zoom,’ I’m asked.

Would I?

Would I????

(Apologies for the multiple question-marks.) (Again!!!) (But, honestly, there are situations that merit them.)

‘I’d love to!’ I say. ‘After all, I’m probably never again going to get the opportunity to ask Tweedy about his Bottom.’

(For professional reasons, I decide not to pursue questions about Jeremy’s Puck.)

‘The only thing is,’ I say, ominously, ‘I’ve got the cheapskate version of Zoom. You know – the one where you’re thrown off after 40 minutes.’

Remember this, dear audience. It is known – in the trade – as dramatic irony.

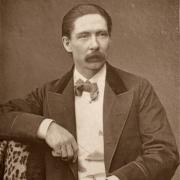

JEREMY STOCKWELL – theatre director, performer, teacher, writer; all-round good egg – and I are having a deep conversation.

He’s pronouncing ‘the Ruhr’ – in Germany, where he lives with his wife, some hens and sheep – in a way I could repeatedly listen to on loop. The last time I heard it spoken about was in fifth form geography where – had only my teacher (Mrs P Clark with an e) managed such a rich series of ‘r’s – we would have been far more keen to hear of its industrial heritage.

Jeremy is describing to me his upcoming roles in MSND. (No offence; it just takes an age to type out each time.)

‘The great joy is that it’s an ensemble piece and, therefore, we have to double up – not just by putting on a different hat or a pair of specs but actually (and this was stressed by dear director – an inspiring chap – Paul Milton) real characterisation.’

(Everyone doubles up apart from Tweedy. He’s all Bottom.)

Jeremy is, quite simply, fab. He’s done lots of work on radio, telly; even Spitting Image.

‘And certainly, when I was teaching at RADA, which I did for 30 years (My god! Am I that old?), talking about how we engage physically with a role to get the words off the page to the stage in a physical way.’

If Shakespeare becomes academic, he says, we’re all stuffed.

‘Acting is not an academic exercise: it’s a visceral, physical, muscular exercise.’

As if on cue, the handle ‘Tweedy the Great’ appears, asking to be admitted to the Zoom call.

‘Hello, darling. How are you?’

(Jeremy, not me.)

‘Am I there? Oh, I’m here! I completely forgot!’

Forgot?

Forgot??? (Again, sorry.)

‘No,’ I say, sternly. (Because I’m not having this.) ‘For the purposes of this interview, you CANNOT say you forgot. Say that an urgent phone call happened.’

‘I went out and I lost the house keys. I had to retrace my steps,’ he says, presumably missing out the bit where he went to pick up his keys from the pavement, got entangled in sticky tape, accidentally welded himself to his briefcase; then fell over with his keys just out of reach.

Tweedy is sporting his trademark orange tuft, plus a pair of glasses so huge, they’d make Boris Johnson look like a boffin.

‘I do want to ask about your Bottom,’ I say, snatching the earliest opportunity.

Tweedy bends over, filling the camera with a trouser-clad derriere roughly the shape and size of the Ruhr.

‘Katie,’ Jeremy sighs, ‘weren’t we having such a lovely intellectual conversation? It was flowing.’

LOOK. I’m promising you an absolute treat with Paul Milton’s MSND. For a start, he’s put Tweedy in charge of the physical comedy. Genius move.

‘And I dare say myself and Jeremy might play when we’re not meant to.’

And why not. As Jeremy points out, Shakespeare is only as much Shakespeare as the Bible is the Bible: fragments, a patchwork of remembrances, different accounts:

‘So, when a clown comes on stage – someone like Max Wall or Tweedy or Ken Dodd, or Marcello [Magni], God bless him who, at the Globe, was Mark Rylance’s clown – then things take off in new directions without necessarily changing the words. Though it’s all right to change the words.’

They have very different memories – the two of them – of their own first encounters with the Bard.

Jeremy grew up surrounded by theatrical folk – mostly of the variety variety. His dad was an actor, who read to his children, and encouraged them to read and learn the plays. Even aged five or six, Jeremy loved them: ‘Yes, because it’s stories; stories. One of my sadnesses is I didn’t get to see my father in Shakespeare. I’ve only ever seen him as a tap-dancer, a comedian, a compere, a singer, and a musician, so I didn’t really know that part of him. But, certainly, growing up in bohemian theatrical conditions, I knew Shakespeare very early on.’

Tweedy’s background was far more conventional. (Not a word you’d employ multiple times in a Tweedy context.)

‘This is what I think puts a lot of young people off – I’m not great at reading because of my focus. And having to study Shakespeare in English at school, before you’ve actually watched it, is completely the wrong way round.’

The stand-out for Tweedy was going to the Globe to see Comedy of Errors. ‘That was genuinely funny. And that’s why I think it would be good, with this production, to encourage young people to see it that haven’t necessarily read it or been made to read it; made to study it.’

And what will children get out of this particular MSND?

‘Go on, Tweed.’

‘Oh, thanks…

‘My dog’s kicking off now. [*Distant barking*] I’ve forgotten the question.’

(Or just show me your bottom again, Tweedy. Whatever you’d prefer.)

‘…It’s making that stepping-stone to get them interested and having lots of visuals to keep their focus. Because kids’ focus nowadays – adults as well; as you can see – is terrible. They’re bombarded with images: you start watching something on TikTok and, if it doesn’t grab you in 10 seconds, you watch something else. That’s not a great thing because you miss so much. That’s the beauty of live theatre: you are sat there and you can’t swipe it off.’

‘We had the great good fortune of a telephone going off in Waiting for Godot.’

‘That was a gift.’

So, what did they do?

‘I said, ‘If it’s Godot, pass it up here’. We could have done 20 minutes, but we thought best not.’

IT’S PAUL MILTON I worry about.

He gives me a wonderful quote, before we start, that goes:

We are really excited about working with Tweedy and Jeremy again, following their great double act in WAITING FOR GODOT. Tweedy, of course, is well known as a circus clown; but Jeremy also comes from a rich showbusiness family, with his roots in variety and music hall. With the two of them on board, we’ll have a load of fun creating physical theatre and comedy routines to augment Shakespeare’s classic text.

Which doesn’t at all say: Blimey; what have I let myself in (again) for as director.

But, you know.

‘We were quite well-behaved in Waiting for Godot, really,’ Tweedy says.

‘I’m not sure we’re going to be as well behaved in this,’ Jeremy concedes of MSND. ‘Some naughty things happened in rehearsals, which we won’t go into. But this play makes you naughty.’

Hang on a mo! You can’t say that and then refuse to tell me.

‘Off you go, Tweeds.’

‘I can’t remember anything naughty.’

‘OK, I’ll give you one,’ Jeremy says. ‘When we were a bit hurried, wanting to do a run-through; and our lovely very, very patient – patience of a saint – director Paul Milton was somehow locked out of the rehearsal room, I think in the rain. And banging on the door. Of course, we couldn’t hear him.’

(Of course! No one can hear somebody banging very loudly on a door.)

In fact, I say – sternly for the second time – I happen to know Paul Milton; a gifted director: ‘And this is going to go straight back to him.’

‘Well, he knows,’ Tweedy points out. ‘He was there.’

WE TALK OF many things.

About the importance of failure, as embodied in the clown.

‘Wasn’t it Beckett who said, ‘Fail, fail again, fail better’? I haven’t achieved anything in my life so much and so well as when I fail. But, by fail, I don’t mean absolute abject pulling-what’s-left-of-my-hair-out.

‘Just screw up! Fall on your arse…’

Bottom. Bottom.

‘BUT in our current education system, it’s not about failure; it’s about success; getting it right. And it is this idea which narrows children; they become reduced.’

And we discuss the lunacy of cutting back on the arts, even though we saw in Covid what the lack of live performance did to us; even though we know that children’s mental health is in tatters; and that theatre/the arts are tools to help.

‘The arts are being cut back because the Government doesn’t want free-thinking people. It’s easier to control people if they’re not reflecting the grievances or the delights of society. They don’t want love; they want fear, and fear is the opposite of love.

‘…Whereas the clown comes on with a big heart; I don’t want to blow smoke up Tweedy’s bum…’

Bottom.

‘But when you look at Tweedy on stage, you get it. It’s real life.’

*You have two minutes remaining* my cheapskate Zoom screen rudely interrupts.

Tell you what, I say to the two of them, I’ll resent a Zoom link – bosh – and we’ll have 10 minutes more.

There follows:

Jeremy and I in one meeting.

‘Tweedy has joined a meeting’ (but not ours).

I find Tweedy and lose Jeremy.

‘We seem to be able to have you or Jeremy – he’s in another meeting,’ I inform Tweedy, who patently knows this.

Then – hooray! – I hear Jeremy talking to Tweedy.

‘No, sorry. You were just hearing my voice message from Jeremy.’

*Jeremy has joined another meeting*

‘If this is a Tweedy prank…’ Jeremy says, finally joining us, looking understandably harassed.

‘I’ve not done anything! It’s just my presence.’

We finish with a time-machine. (Brave, considering even Zoom was beyond our capabilities.)

Jeremy would travel back to the Bay area of San Francisco, late 1960s: Alan Watts’ houseboat, the Vallejo. To hear his one-time teacher and philosophical entertainer talk again.

Tweedy would see Grock.

‘I’ve met various older people that had actually seen him and they just sort of lit up when they spoke about him. In their eyes, there was complete love for this person they didn’t know: they’d just seen him on stage.

‘He was pure clown.’

Can’t think of whom (BEM; King Charles’s list) that reminds me of…

Well, I thank them both, warmly, ‘I couldn’t have enjoyed that more…’

Wait! I say. ‘Actually, I could have enjoyed that more.’

The 40 minutes was great. The 10 of trying to find them both on Zoom was dire.

Well at least, Jeremy points out, it was that way round.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Paul Milton, runs at Cheltenham Everyman from March 21-30, everymantheatre.org.uk, before going on tour

Tweedy’s Massive Circus (‘full disclosure: it’s tiny’), solo show, opens in Stratford as part of the RSC programme at the end of May, before touring: tweedyswebsite.com; rsc.org.uk