When Gloucestershire farmer Eric Freeman died last year, there was nowhere big enough to hold a wake. So this month Clifford – his son – is holding a festival to celebrate the life of a man who championed so many of the county’s rural traditions.

‘ON BUILDING A HAYRICK: They had to build a staddle to start with: this was hedge trimmings, old grass and dry stuff on the bottom to stop the damp getting up through… they would build round but they would build it up to where the eaves were going to be; and they built them gradually out so that, when the wet came down the roof, it dripped on the floor and didn’t run down the rick. To build the rick up like that, and to be safe, was a very skilled job.’ Gloucestershire farmer Eric Freeman (September 8, 1932-October 29, 2023): from Thumbsticks and Frails, Some of Eric’s Reflections on Country Life.

Clifford Freeman is speaking to me via Zoom from the Isles of Scilly. The weather was gorgeous yesterday. He grimaces slightly: today, there are no flights in or out: ‘Which is causing us a bit of a problem!’

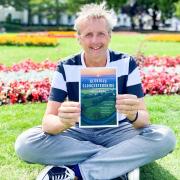

Some days, Clifford works at home on 16th-century Evere’s Farm, Redmarley, beside the River Leadon (just downstream from where good old Dick Whittington tied his red knapsack and summoned his cat). It’s the area where the Freeman family have lived for the past 100 years and more; the farm where Clifford tends (amongst other things) his herd of 360 Gloucester cattle. Other days, he’s running his holiday lets, hotel and restaurant on the beautiful unspoilt islands that dally off the tippy-toe of Cornwall. A second work-place also surrounded by water: but, this, the brilliant turquoise of the stormy Atlantic.

The two places meet in the beef from his very special herd: ‘The meat from the Gloucesters is exceptional. So much so thatit’s the only meat we serve in our restaurant.’

His late dad, Eric – a saviour of the Gloucester breed (one of the country’s oldest and rarest) – never ventured far from home. ‘I think dad went abroad two or three times in his life: to Switzerland, as a Young Farmer, skiing. And to Germany, to an agricultural show once… He went to Normandy once as well. ‘That was his lot. He didn’t go anywhere else.’ Didn’t need to. Everything he loved and needed was around him in Gloucestershire. But he did visit the Isles of Scilly, where he tucked in at Clifford’s beach barbecue restaurant with gusto. ‘He was in his late eighties, at the time, and you’d expect someone like that to be “meat, two veg” and nothing else.’

Not a bit of it. ‘He thought the food was amazing.’ The memory of the trip conjures up another scene. ‘He came to Scilly, and there was no electricity; so he sat talking to this old chap, who was burning a candle. And this chap said to dad: “Timeless. A candle is timeless”.’ Another memory follows hot on the tail. ‘Dad moved out of his farm into a home two years ago. We’d been in and out of the house in the meantime; but we’d been putting off clearing it out for ages. The first day we really got round to it, we walked into the kitchen – and there was a battery clock… still ticking.’

TIMELESSNESS. And time’s inexorable ticking.

A contradiction that perfectly summons up the life of Eric Freeman.

When Eric Freeman was born at home in 1932, the doctor said he was the longest baby he’d ever delivered. Poykes Farm, in the countryside outside Newent. Newent where, down at Cleeve Mill, the miller was still rolling corn by the waterwheel next to Ell Brook. (‘I can see him now, Mr Lawrence the miller, standing in the doorway of the mill with flour all over his cap and down his coat.’)

Old Cecil, one of their farmworkers, was rarely seen without a waistcoat flapping in the breeze: underneath, a cotton striped flannelette shirt. Once, Eric reminisced, Arty Clifford from Gorsley had to go all the way into Gloucester, putting on a tie and fixing a collar onto his old clothes for the occasion. ‘He came back to start doing some work and said: “’Ang on a minute. I’ll have to go and get all this clobber off before it gets mucked up”.’

Those were the days of rolling cherry orchards; trees laden, too, with apples, pears and cider fruit. The days when birdlife was stupendous. A neighbour would take young Eric picking yellow dandelions for bubbling, fruity wine: gathered into old wicker baskets on the field behind the house. Into her rice puddings and apple tarts, she’d add fragrant twiggy cloves, which she’d call the bee’s knees. ‘Be careful you don’t eat the bee’s knees!’

Gloucestershire people had a language of their own. A quoist was a woodpigeon; an unt a mole (and a professional mole-catcher an unty). Crazies were buttercups; dry, rotten wood was daddocky; a small culvert under a gateway (in which foxes would hide from the hunt) were druffs. Horses – or ’osses – were king of the farm; the fields full of working people. Yet, even then,the future was catching up. On December 28, 1934, Eric’s grandfather – a farmer, too – was busy transporting pigs and cattle to slaughterers in Birmingham. He got out of the lorry to cross the road and was hit by a car: ‘Which always seems most unusual to me,’ Eric would say. ‘In those days with very little traffic.’

Eric loved sharing these memories of a rural Gloucestershire of times past. A countryside defined by respect for the earth; but of no sentimentality.

These people had to live; and life was often bordering on brutal. Struggling through snow, axe on shoulder, to break ice on the troughs – teeth-rattling winter days – so cattle could drink. No water-pipes in the fields. Some men wore mittens… if they had them; there few gloves to be had. Cows would be milked by candlelight.

Kids were let off school when needed for work. If something exciting was happening on a farm, word shot round like lightning telegraph (no texts).

A favourite job was killing vermin – mice, rats, rabbits. The children would streak off on bikes, clutching favourite trusty sticks. They’d follow binders round; linger – sharpeyed – as crops were cut and rabbits trapped in the middle. As the terrified creatures tried to escape, the children’s war-cry would go up: ‘Arry, arry, arry’; knives would be pulled from pockets to notch the kill-rate on their sticks.

Some might think that barbaric. But we – of plastic-wrapped convenience – cannot judge: rabbits were a valuable part of the diet in those hungry days.

Clifford, just turned 60, remembers the red-letter day when the Dowdeswell sisters sold their herd of 33 Gloucester cattle from the farm at Wick Court down Overton Lane in Arlingham. Or, at least, he remembers those intriguing sisters.

It was October 25, 1972, and Eric – who’d always been interested in old breeds – went along to the sale, frightened to spend too much money: he’d already got cattle; probably didn’t need more.

‘Gloucestershire Cattle’, the Farmers Weekly notice termed them. These were the remnants of a long-proud breed; even back in 1840 they were teetering on the edge of extinction. One of the older cows, Daffodil, reminded Eric of a tiger with her stripes. She would go on to found a new dynasty. And so – in his way – did Eric, along with fellow pioneers such as the late, also much-missed, Joe Henson. They held their inaugural meeting of the Gloucester Cattle Society the following year at the home of Mr Teesdale, who’d also been at the sale.

So they were the ones – along with the sisters – whom we can thank for saving this noble breed, with its dark mahogany body; its black head and legs; a white stripe from small of back, down over the udder; upsweeping white horns, tipped with black. Way back in the 13th century, they were numerous in the Vale, prized for their milk and beef; strong draught-oxen too.

Equally intriguing were those Dowdeswell sisters, who once described themselves to the then-Prince Charles as: ‘The fools that kept the cattle on’. No fools, they.

Clifford’s abiding memory – he laughs as he says it – is of them bickering. But more than that.

‘Goodness, this is a really distinct memory. I remember the big oak tree [that has guarded the farm for hundreds of years], hollow in the middle. They told us it was 1,000 years growing and 1,000 years dying.’

Once, the sisters said, they found an airman hiding in it during the war, using its woody walls to keep warm. ‘And the privy! It was a moated farmhouse and the privy used to hang over the moat. There were three different sizes of hole on this one bench. Everything went straight into the water.’

The settle in the kitchen had a bullet-hole in the end. And then there’s the secret passage, which the dashing Earl of Leicester is rumoured to have used to make tryst with his lover, Queen Elizabeth I, in the bedroom where she slept below. ‘Those were the things I remember because they fascinated me as a kid.’

CLIFFORD FREEMAN IS MAKING LISTS (at least in his head). On Saturday, May 11, from noon at Everse’s Farm, he’s holding a festival to celebrate his dad’s life. To celebrate the life of a farmer whose determination to preserve the best of rural Gloucestershire – the breeds, the traditions, the farming knowledge – touched the hearts of so many.

So many that, when Eric died last autumn, there was nowhere big enough to hold the wake. So this festival is the wake; one that would have delighted him.

But – and here’s the head-scratching – how to make sure all that Eric stood for and was involved in is represented. The Rare Breeds Survival Trust, of which he was a founder member; Gloucestershire Federation of Young Farmers’ Clubs (he was county president for years); wassailing, Morris dancing, harvest home.

Eric understood the weights of the axes needed to fell each part of a tree before chainsaws arrived to do the job in no time.

He appreciated the complexities of the old horse plough that a skilled man could tilt for corners without even touching the handles.

Not a Luddite, though. He ran a successful poultry business where, for a time, he and his business partner were forerunners in modern processing methods. It wasn’t really for him, though. Farming died a partial death on August 1, 1979, when EU regulations came into force. Regulations that ran counter to so many of the old, tried and tested ways.

‘The Cotswold Sheep Society, Gloucester Cow and the Gloucester Old Spots,’ Clifford continues, ticking his dad’s involvements off on his fingers. ‘Then the Cotswold Carthorse Society… Obviously the Morris men.

‘There were the nature groups: Butterfly Conservation; FWAG [Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group]; Bat Conservation. It just goes on and on…’

He pauses before beginning again. ‘Dymock Poets… All kinds of stuff. They’re not all going to be there, and there are some routes I haven’t even gone down.’

What’s more, the festival is going to be full of activities – not just standing around chatting (though there’ll be plenty of that). Heavy horses; shearing demonstrations; a chef creating meals based around produce from the farm. A proper country show.

Eric was all for sharing his love of tradition; all for education. ‘Dad would have loved the idea of the festival. It’s what he was all about.’ Eric Freeman straddled a watershed: in a sense, his early memories went back hundreds of years: so little had changed in his youth.

‘He told me about the day he left school at 16 – a bit later than most,’ Clifford says. ‘In the afternoon, he went to lead the horse on the horse-engine, lifting the hay up into the rick; a horse engine with a pole. That is just incredible now to think that was how hay was lifted.

‘There are many things happened since then to do the same process; but that was horse and, in his lifetime, that was normal.’

Many of the things Eric said were laughed at in the 1970s; yet, today, they’re coming full circle. Not that Clifford’s own memories aren’t without humour still.

‘I came out to the farm one day, and dad had got his heavy horses with a horse-drawn muck spreader… he was loading it up with a tractor. ‘I said: “Hang on, dad. I don’t understand what you’re doing here.” ‘He said: “Well, spreading the muck.” ‘I said: “With horses?” ‘“Yes.” ‘“But you’re loading up with a tractor.” ‘“Yeah, well, it’s hard work loading by hand.”’ Clifford laughs. No idea why his dad didn’t do the whole job with a tractor. Except, of course, this was Eric Freeman. ‘And some things he did just to be bloody awkward.’