Clare Hammond is describing a scene that sends shivers down my spine. As a highly-acclaimed concert pianist, she’s used to performing to audiences of all sizes and persuasions, in all kinds of locations: the Barbican, Wigmore Hall, the National Gallery, in hotels and school halls during festivals; all over the UK, throughout Europe. (This year, a Canadian debut.)

But this particular performance is different.

No green room; no busy engineers setting up sound and lighting; no delicious squeaks and rumbles from an orchestra tuning up.

Instead, she has lugged her electronic piano past fearsome gates, security checks, numerous locks, and an endless bleakness of concrete corridors, before arriving in a chapel.

A prison chapel.

Here, she plugs in her piano as rows of men file past to their seats.

Clare has no idea how her performance – the first she has ever done in a prison – will be received. She breathes deeply… and begins.

‘I played two pieces: Chopin, Debussy; quite virtuosic showpieces. Next I had a piece by Schubert that was very quiet and very inward-looking. The audience still wasn’t quite settled…’

(Or, as she writes more fully on her website: some were listening, others conspicuously bored; one group of young men was mucking around together.)

‘I was worried that they would not engage,’ she tells me, with simple understatement.

‘So I chose first to speak about Schubert’s final days. How isolated they were, and how dramatic it all was.’

How, at the age of 31, Schubert had died in raving delirium, with scant nursing care, in a room so badly heated that damp was running down the walls. Yet how, even as he descended into the blackness of his terminal weeks, he had composed music of sublime beauty.

‘It was really interesting because I could just sense the attention in the room switch. Suddenly, everyone was on board with this piece, which was six minutes of very quiet playing. And I could hear a pin drop…

‘I think that was the most magical moment I’d had during a concert.’

In theory, I should be utterly terrified of meeting Clare Hammond.

‘A pianist of extraordinary gifts’ (Gramophone); ‘immense power’ (The Times); ‘fascinating magnetism’ (BBC Music Magazine).

But, no. No – I don’t mean because of those reviews, awesome as they are. (As awe-inspiring as she clearly is.)

It’s another from the Times that gets me: ‘Exudes the air of someone who sprinkles her morning cereal with iron filings.’

Good lord. It makes Clare Hammond sound like a cross between Boudicca and Margaret Thatcher on a bad day.

Except that…

She includes it in her Twitter (X) bio. And if you think that indicates a sense of humour, you’re really not wrong. When we meet at Stroud Brewery, she’s funny, open, honest and with the readiest of laughs.

‘Oh, I’m terrible at crosswords! Sorry!’ she says, when I push my Times puzzle in front of her as I nip off to order sparkling water (for Clare) and a pot of tea.

So what was the iron filings review all about?

‘I’ve no idea what they meant but it tickled me.’

We’re here to talk (amongst other things) about the programme she has prepared for this month’s Cheltenham Music Festival: a delightful synthesis of darkness and light. Of sunlight and shade. Music of brooding uncertainty that gently shadows pieces of forthright optimism.

Fauré (Nocturnes), Beethoven (Moonlight), Mozart, Debussy, Clara Schumann; études by Cécile Chaminade; a world-premiere, commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society for Cheltenham Music Festival, of a work by Sun Keting…

Wait.

Chaminade? Sun Keting?

‘Generally, when I’m constructing recital programmes, I tend to base them around core works that I know people will love and that they know already - so there’s something familiar there.

‘Then I’ll combine them with less well-known composers; often with contemporary pieces. People love experiencing something new.’

What’s more, even for audience members who feel nervous about coming to a concert that includes an unfamiliar composer: ‘It’s always those pieces people talk to me about afterwards.’

Chaminade – huge in her day, back in the 19th and 20th centuries – was a French composer of more than 400 works; the first female composer to be awarded the Légion d’honneur, instituted as an order of merit by none other than Bonaparte himself. (We’ll get to the wonderful Sun Keting in a few moments.)

‘I regularly set time aside to research composers that I haven’t heard of – follow the links; composers I’ve heard other people perform. But Cecile was one of the few I had heard of early on.’

Growing up in Nottingham, Clare would be taken by her mum to a ram-packed second-hand music shop full of musty, dusty, intriguing folios from the 20s and 30s. They’d buy in bulk, and Clare would play through them.

‘I remember Chaminade clearly because there was a publicity photo on the front [of a folio] where she had a massive lace collar on that fascinated me. I was seven or eight at the time, and I couldn’t understand why a grown woman would wear something so frilly!’

But why did a woman - visible and admired in her day - drop so spectacularly from public view after her death? (Albeit now with a growing revival.) Misogyny?

‘It’s always difficult for composers to establish reputations during their lives and after their death. Chaminade was in a good position in that she was clearly switched on; she had a business mind so she was already well known during her life. But it really helps to have a widow to promote your legacy after you die.’

Vaughan Williams had Ursula; Andrzej Panufnik had Camilla (whom Clare knows; she has a particular affinity with Panufnik’s music).

‘I don’t think Cécile had that.’

But, yes, a kind of misogyny plays its role. (A misogyny still visible today when you examine the fact that would-be concert pianists are 50/50 male/female in college; 80/20 in subsequent careers.)

‘Barbara Strozzi [an Italian of the Baroque period] composed a phenomenal amount of music, but it wasn’t collated in any logical way after she died because she hadn’t had a career in church music, which is how most of the male composers got established.’

Hélène de Montgeroult – another Clare favourite – had one son, who didn’t collect her correspondence or manuscripts upon her death in 1836, ‘because he didn’t realise that they were significant.

‘We haven’t lost it but it’s taken much longer for it all to come to light because it was scattered.’

Yet, to return to Chaminade, here was a pioneering woman; one of the first to make rolls for pianolas; one of the first people to make gramophone recordings.

(A controversial thing to do in the classical world of the time, moreover. Pianist Artur Schnabel was traumatised by the thought that records might be listened to by people not wearing evening dress.

‘I know,’ Clare says. ‘I think about that when I listen to stuff in the bath.’)

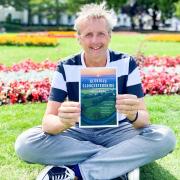

And Sun Keting? Very different.

‘Yes, lovely Rockey Sun Keting! I met her in London a couple of weeks ago. She’s great fun. I’ve heard a lot of her works, but only a couple of things for piano, which were written a long time ago: her style has changed a lot since then. So that’s unknown; it’s exciting.’

Hang on! (And we’re in early May here.) Isn’t that daunting (rookie question, I know), having to perform a world premiere to a huge audience when Clare doesn’t have a clue what the piece is a bare few weeks beforehand?

She laughs that ready laugh.

‘I did find it nerve-wracking when I was starting out. I’ve done enough of those now that I’m used to the process, and it’s very rare that you get a real dud! I have confidence that Rockey will write a tremendous piece. She’s deliberately writing something that fits well within this programme and complements the other works I’ll be playing. Usually, when I’ve performed new pieces, they’ve been standalone entities. This is the first time the composer has taken a context into account in such a detailed way.’

I’m fascinated by the life of a concert pianist. A life of extremes, so it seems to me. At the end of our chat, Clare will be picking up her two girls from primary school in Stonehouse. (‘The teachers are wonderful; they really create a community feel. We’ve got lots of friends here.’) In a couple of weeks, she’ll be jetting off to Poland for a concert with Wroclaw Philharmonic; then a solo performance in Germany in August; plus all sorts of UK gigs. In September, she makes her Prom debut in her home town of Nottingham (the first time they’ve held a BBC Proms there).

‘My husband [Peter, who works in public health research] is wonderful - he does most of the childcare, most of the parenting at home, and holds everything together. If I’ve been away for a long time, he’s utterly exhausted when I get back so I’ll take over…

‘I will say this: It’s far easier doing my job than looking after children, especially when they were very little. It was like a holiday, going away for work, because I knew I’d get a night’s sleep!’

Her dream, as the girls get older, is for the whole family to accompany her (outside of school times).

‘But even now, if I have a concert during the day that’s within a drive of home, they’ll come. So I was playing Grieg with the CBSO a couple of years ago, for a matinee, and they came to that, which was lovely.’

Were they amazed?

‘They take it completely for granted. They think it’s normal.’

Because of childcare, even Peter can’t accompany Clare as much as they’d both like. ‘But, if he is coming, he keeps away until after I’ve performed. I’m terrible company before a concert. He says it’s awful!’

In fact, it was family that prompted a significant change in direction for Clare. In 2017, she and Peter moved from the Hertfordshire border to Gloucestershire, to be nearer to Peter’s parents who’d retired here.

Herts was great – but more as a practical centre from which to commute.

‘I’d never felt grounded since I left home at 18. So, when we moved to Gloucestershire, I was very keen to become more connected to the community; to feel I belonged to the place.’

She got in touch with Nick Steel, head of school music for the county council’s Gloucestershire Music, and together they began collaborating on a series of performances Clare could give to primary children – something she continues to this day.

‘We always choose schools with a lot of pupils on pupil premium [for more disadvantaged children] that haven’t necessarily already got a lot of music provision. It’s been a wonderful experience for me, partly because I feel I know Gloucestershire much better through it.’

The prison concerts found their naissance in this period, too.

It was during these performances – often to audiences that had never heard live music before, never mind classical – that Clare discovered the power of narrating a snapshot of the stories behind the pieces.

For children, that might involve giving a visual image – such as fireworks, an idea she uses to help them follow a piece by Unsuk Chin, a South Korean composer, which builds up gradually before exploding into a burst of colourful sounds: ‘The enthusiasm is quite astonishing because, for lots of people, it’s just so weird; they’ve never heard anything like it before.’

In prisons, Clare’s introductions can also include her own experiences of mental ill-health: a bout of anxiety, after pushing herself too hard in her early 30s; severe post-natal depression after the birth of her second daughter.

‘Which will so often resonate with people.’

Access to classical music might at times be elitist; the music most definitely is not. Which is why it’s vital, Clare Hammond says, that classical music be taken to communities that don’t necessarily have that access.

‘In South Korea, classical music is hip; something young, cool people engage with. And the music itself is just extraordinary: everybody should have access to it.’

Human connection; emotion; mental well-being; intellectual development. And sheer, unadulterated joy.

‘Classical music can enrich lives in such a deep and meaningful way.’

Clare Hammond will be performing at Cheltenham Music Festival on Saturday, July 13, from 11am-1pm in Pittville Pump Room: cheltenhamfestivals.com/music

For more on Clare Hammond, visit clarehammond.com, where news and information on new charity Gloucestershire Piano Trust – supporting Clare’s community work in schools and prisons – will be available.