Sally was first, back when we were newly married. I’d done an article on a local dog shelter and made the rookie error of describing it in heart-rending detail to a sobbing Ian. Before I could say ‘Not on your furry Nellie Duff’ (great name for a dog; don’t mention it), we were standing outside a cage where a brown-and-cream springer cowered in a corner.

‘We’ve only got this spaniel,’ said the chap, showing us round.

‘Heavens! Will she be too quiet?’ we wondered, as she silently stared at us with mournful eyes.

Reassurance came hot on our heels. Pretty much literally. Sally spent every waking second of the next 13 years barking at us to throw another stone. (Don’t tell Graeme Hall.) Character-wise, my brother summed her up. Were she human, he said, she’d smoke; but only socially.

Josh, our next springer (another rescue, as they’ve all been), was brighter than both of us put together. Cerebral and dignified, he had zero interest in being a dog. Throw him a stick and he’d observe, ‘Well, that’s gone, then.’

And now Ruby, our cocker: 95 percent fur, 5 percent intellect; who has me wrapped around her humongous paw. Ian can’t understand why she puts on weight, even on a diet. So strange.

Graeme Hall, aka the Dogfather, is driving through the Cotswolds.

‘And you’re going to love this!’ he chuckles. ‘Halfway between the Rollrights and Adlestrop: that’s where I am.’

He used to live in the Cotswolds. ‘In Charlbury, when Charlbury was a Cotswold town that nobody had heard of. But now it’s THE place to be. Referenced in every Sunday Times article about the Cotswolds.’

Not that he’s moved too far away. ‘I’m in a village outside Banbury, which actually looks like a Cotswold village. It’s just a bit cheaper – I am a Yorkshireman.’

I love this. We’ve been speaking on the phone for approx one minute, and he’s referenced the Cotswolds six times. (Don’t bother counting. I left some out.) He’s using positive, keywords for me, in a clear tone of voice. And already I feel calmer, happier, with little inclination to chew the phone cable (in some interviews this feels like a valid option). Only slightly concerned, as I continually ask questions, that he could mark me down as attention-seeking and send me straight to my bed.

I’ve caught him on his way to Cheltenham Science Festival, where he’s giving a talk.

‘I’m not a proper scientist and I’m very conscious that I’m being interviewed by a fellow who’s a professor. There aren’t many Yorkshiremen who are serious scientists, and that’s because we’re all brought up to believe we already know it all.

‘You can always tell a Yorkshireman but you can’t tell him much.’

Crikey. And me from Lancashire.

‘That’s all right. We’re both down South so we’ve got to stick together.’

In one of his Dogs Behaving (Very) Badly episodes – his hit Channel 5 dog-training show about to film its seventh series – he was on his way to a house in Burnley. ‘And it was absolutely tipping it down; no disguising the fact on camera. So I was walking along to the house, with this big umbrella, thinking, ‘Ugh. Welcome to Lancashire.’ I get to the house, knock on the door and – this was not at all planned – the fellow walked out and he says, ‘I see you brought your Yorkshire weather with you, then.’

‘It made it to the cut. I was quite pleased with that.’

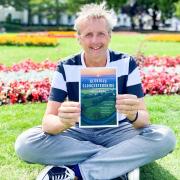

I’ve just read Does My Dog Love Me? Graeme’s book about how dogs see the world – and it’s a great book… I mean, to be honest, it probably should be called, ‘Boy, do I flipping love my dog!’ For it’s a book that tells how, even 11,000 years ago, we were super-soppy about them. We might not yet have discovered ancient remains of any hair-encrusted sofas; but, even in the first known settlements in the Med, dogs were found buried alongside humans.

It’s a book about how we’ve grown together (their brains, probably unsurprisingly, are strikingly similar in structure to ours: a hippocampus to remember things; an amygdala for arousal, excitement and fear. (And, in my own case, an over-developed area in the pre-motor cortex associated with stones)).

And how the bond between us is pretty unbreakable. I challenge you to read, dry-eyed, about the beagles, stolen from South Wales, and found three years later in Berkshire, some 200 miles away. When they were reunited with their original owner (we’ll come to that word shortly), they went absolutely nuts. Or the dog in Texas, spooked by fireworks, who was found seven years later in Florida. By this time so aged she could barely walk, she came to life at her owner’s (see above) voice: ‘licked his hand again and again, and inched her body as close as she could to him’.

Excuse me for a moment.

It’s about dogs that howl; dogs that get jealous and depressed; dogs that bite. It’s also about the really clever tricks dogs have learned without being taught: developing moveable eyebrows, for one. About how they went from Botox-face to Mr Bean for the express purpose of (my words; chosen through bitter personal experience) blatant emotional manipulation.

Even welling up with tears.

Japanese scientists showed 74 people (don’t ask. I’ve no idea why 74, but it was) pictures of dogs’ faces with and without tears in their eyes… ‘and – surprise, surprise – it was the teary-eyed dogs that got the more positive responses’.

It strikes me, I suggest to the Dogfather, that dogs are far better at knowing us than we are at knowing them.

‘You do wonder, don’t you. It’s certainly true to say that dogs spend a lot of time observing.’ So whereas humans are wordy, dogs are visual. ‘Like when you’re on holiday in a foreign country and there’s a conversation going on that you don’t understand. But you spend more of your time watching people’s body-language and you kind of suss it out: ‘I’m not sure I like that fellow at the bar; but that other one there looks quite funny.’ That kind of thing.’

Sure. But Ruby spaniel – who deliriously greets me, after a rare hour’s absence, with the unbridled joy of those stolen beagles from Berkshire – listens, too. If she senses anyone is leaving, she’s at the garden gate before you can say, ‘Shall we go?’

Graeme’s not far behind on this one. Years ago, he lived with a Jack Russell who’d bark and whine every time he went to leave the house. It took Graeme a while to realise that, before he made any going-out sort of move, he’d start with, ‘Right, then!’

‘Yeah, yeah. They don’t understand full sentences... There are one or two cases where dogs have been taught to understand things like, ‘Go and fetch the red toy’.

‘But they’re brilliant at inferring what’s going on from tone of the voice, facial expressions; all that kind of thing. They’re also really good at spotting routine, which is why your spaniel goes, ‘Ah!* They’re going out. I’ve read the signs.’

*Clarification: It’s more like, ‘Argghhhhh! They’re going out. Forever.’

We’re in the middle of talking about how much we are in danger of letting our adored dogs get away with – more even than children (because we can’t explain things to them in the same way) - when, Boing! I lose him.

‘Oh!’ he says, eventually returning to me. ‘We’re a bit garlicky still. I’m in the back streets of Stow-on-the-Wold. You’d think they’d have a better signal in Stow.

‘Enough money here.’

No one is more surprised at his success than Graeme, just back from Australia where he’s done a second series. ‘I keep pinching myself.’

Especially as he came to dog-training relatively late in life. Never had a dog as a child. Spent 21 years managing factories for Weetabix. But, I’m thinking, maybe it was his seven years as a special constable (ending up as a special chief inspector in Northampton) that particularly helped.

Because there’s more than a touch of Hound of the Baskervilles about him.

Take the time he was called to a domestic. Neighbours had heard a woman scream. ‘Can you check out any intelligence on this address... Yeah. Living there is a man who has just been released from prison. He’s got previous for wounding with knives, and he’s a convicted armed robber. So who’s going to be the victim here and who’s going to be the bad guy?’

‘Well, guess what. It was the other way round.’

Not in any way to compare the two; but just to say that dog problems can be detective cases, too. Such as the collie, who apparently would obsessively stare at himself in any reflective surface. His owner was in tears. ‘Darling, what’s wrong? Come here – don’t do that.’

By a process of deduction (decryption of ciphers, fingerprints, the idiosyncrasies of typewriters, sort of thing), Graeme worked out the dog wasn’t looking directly at himself at all.

‘He’s looking at an angle. So the next question in your head is, if he’s not looking at himself, what can he see from that angle?

‘He can see his owners.

‘Why would he be doing that?

‘Once you ask yourself that question, it’s like: Bloody hell, that’s obvious… A bit of a crafty bugger.’

If he were to stare at his owners for attention, he’d be rumbled. By looking obliquely, he got all the attention he craved.

Elementary.

Boing…the signal drops.

‘We’re on the way down to the Swells so it’s a bit lower. You can have some fun with this article. Write it as a journey through the Cotswolds. ‘Hang on!’ he says. ‘I’m in traffic in Stow-on-the-Wold…’ Then the signal drops as he goes through Lower Swell.’

We talk about loads more. Inevitably.

How dogs recognise their mothers (and vice versa) after years apart.

Which makes me sad. We separate them at such a young age.

‘If you took that to its extreme, you’d say: maybe we ought not to have pet dogs. There are people who think like that.

‘My answer would be, well, look: we’re not talking about wolves anymore. We’ve been living with these dogs, these canines, for at least 20,000 years – maybe more. We’ve created this animal that’s almost designed to live with you. We have a responsibility to them.’

He is, however, sensing a pushback on the word ‘owner’. And – in the same vein - he’s delighted about a recent change in the law creating special offences for dog- and cat-abductions in England and Northern Ireland.

‘Me and loads of other people have been campaigning for years to say, look: when pets are stolen, they should not be treated like property – which is how the law used to treat a stolen dog.’

He’d like to see new regulations around breeding: ‘Perhaps there should be some kind of qualification. At the moment, anybody can breed any number of dogs with any number of problems.’

He’s also done an about-turn on dog licences. Used to be against them as unnecessary bureaucracy. And OK, he admits: we have laws about car MOTs and insurance that some people still constantly flout. ‘But where would we be if there was no law – no driving licences or need for insurance? So I’m beginning to think we should all pass some basic test; show some sort of basic knowledge in order to be a pet owner.’

So. Final question: Graeme Hall certainly seems to be able to see directly into the minds of dogs. But if he could speak to them, and if they could reply…

‘I’d have loads of questions, wouldn’t I?’

Can you tell the time? Do you understand my methods? Can you see the telly? (One dog in Australia went bananas at the telly. So Graeme sat with him on the sofa and put on Dogs Behaving Badly to see if he was barking at dogs on screen. ‘Purely by chance, I was wearing the same jacket as I was on the telly. The dog sat next to me on the sofa, watching, lovely and calm. And then it started to go: Hang on a minute… Telly, man, telly, man. It was really funny – like a cartoon character.’

More poignantly: ‘With my own dogs, I’ve got two – about two weeks ago today, we had three dogs. We lost a very old boxer who was 13… That’s all right. You can mention it. He was deaf in his old age, bless him. Very old man.’

The remaining two dogs are Johnny, a 15-year-old mixed breed; and a very aged Patterdale called Tish.

‘She’s gone blind in her old age and I think she’s got a bit of canine dementia. I’d love to be able to ask Johnny: Do you understand that she’s blind? I could see last night she was bothering him; walking round in circles, walking into him, and he was going, ‘Oooher!’ He’s not a nasty dog but he was like: For god’s sake! I was like: Mate, she can’t help it… I can’t explain it to him.’

We could chat for ages about our favourite subjects; but he’s just about to arrive at Imperial Gardens for the festival.

Tell you what, he says.

‘You can end it with a thing about: used to live in the Cotswolds. I love the Cotswolds – the only thing is: the phone signal.’

For more on Graeme, visit dogfather.co.uk

For Cheltenham Festivals: cheltenhamfestivals.com