Walk along the banks of the river Deben, just below Woodbridge Tide Mill, and a cacophony rings out from the former Whisstocks boatyard. In the Longshed, the knocking, hammering and chopping comes from a team of volunteers, members of the Sutton Hoo Ship’s Company, who are tirelessly constructing, by hand, the hull of a 27 metres (almost 90 feet) Anglo-Saxon wooden ship. They’re proving quite a visitor attraction.

Whether it’s cleaving a 6 metres (20 feet) long timber on the concourse, splitting logs into planks, or fixing them to the hull of the ship’s skeleton inside the Longshed, there is plenty to see. And, as they're using the same tools, techniques and materials of the Anglo-Saxon period, it’s not only a phenomenal achievement, it's an intriguing spectacle for passers-by. ‘It’s fascinating for people to watch this taking shape,’ says Angus Wainwright, regional archaeologist for the National Trust.

It is the trust's Sutton Hoo site that has inspired this project. The ‘fossil’ of the ship was unearthed in 1939 during excavation of the mysterious grassy mounds at Sutton Hoo on the eve of the outbreak of war. It cradled extraordinary riches believed to belong to Raedwald, the king of East Anglia in 624AD, in his last resting place. The treasure is now housed in the British Museum and the National Trust maintains the Suffolk site for hordes of visitors to experience each year.

But all that was left of the original ship were the stains of its timbers, the rusty iron rivets that held them together and a lot of unanswered questions. What was the ship used for before the burial? Where did it come from? Had it sailed up the river? Would it have been used in battles or carried cargo? How was it moved from the waterside up the hill to its resting place at Sutton Hoo?

‘There’s a strong archaeological reason behind wanting to get the ship built,’ says Angus. ‘And it was always an ambition that the trust, if it couldn’t build the ship itself, would help and encourage others to do it. Especially if they were going to do it here in Woodbridge.’ The ultimate aim outlined by the Ship’s Company and by all the historians, shipwrights and volunteers involved is not just to admire the undeniable skill and craftsmanship, but to see the vessel launched and seaworthy, to gain valuable information about our maritime past.

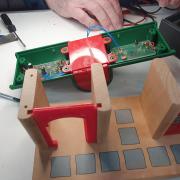

The National Trust photographs of the excavation by Lack and Wagstaff were made available to the team. Now, with planking underway, the trust is getting involved in other ways, giving access to the vital timbers needed, and also recently sending apprentice joiners on a short internship to learn more about the materials, tools and building methods used by the Anglo-Saxon shipbuilders.

‘There have been people at the National Trust who have wanted to see this project come to fruition for about 50 years,’ says Sutton Hoo Ship’s Company shipwright Tim Kirk. ‘So to actually have the apprentices working on this has been brilliant. And young people bring a totally different perspective.’ Their enthusiasm and passion for the project has been evident, though they have had to learn how to use the ancient tools, something Tim himself has had to come to terms with.

'As a modern boatbuilder,' he says, 'when I want a piece of wood, I go to the timber yard, but for this ship I’ve got to go to the forest and find a tree. We spent 18 months searching for the right tree for the keel.' And the search continues. There are specific requirements for suitable trees; they need to be 20 feet long and 4feet in diameter, or 6 metres by 1.2 metres.

As Laura Howarth, Sutton Hoo's archaeology and engagement manager, explains, two oaks donated from fellow National Trust property Blickling were cleaved in front of visitors to Sutton Hoo. The wedges of timber were then further worked into planking for the ship at the Longshed. It’s hoped more will follow.

‘The trees that were felled to support this project were part of a plantation woodland at Blickling,’ says Stuart Banks, trees and woodland adviser for the National Trust. ‘They were planted and managed as a crop, to be harvested and used centuries later for a construction project such as this. We were really pleased to be able to support this fascinating project and reconnect our woodlands with heritage and tradition.’

In the 1800s, the industrial revolution spurred a drive to plant more woodland to support the need for ships to export all around the world. It took about 50 acres of oak woodland to make a ship, so large areas of woodland were planted. A lot of this planting took place in areas such as the Forest of Dean, but many estates up and down the country still have a generation of trees from this era. By the time the trees were suitable for structural timber, the country had moved on to metal ships, so Britain still has part of this legacy in countryside estates.

‘As the build of the ship continues to grow,’ says Laura Howarth, ‘so too will our partnership, as this project becomes a fascinating new chapter to the Sutton Hoo story.’

NEW SKILLS, NEW TOOLS

Apprentice Rowan Kitt

‘This is very different to anything I’ve worked on before,’ says Rowan Kitt, 19, who is on a three-year apprenticeship with the National Trust in Devon and Cornwall. Typically, he might work on repairing and replacing rotten gates, windows and doors, staying true to the original materials and design, but using modern machinery.

‘You’re not going to use an axe so much in modern work,’ he says. ‘But it has been very interesting and good to learn these skills. It’s a lot of work but very rewarding when you see what you’ve got at the end of it.’

Rowan realised his love for woodwork during lockdown when he started making garden planters. He answered the advert for the apprenticeship scheme after completing his A-levels. ‘I’d spent a lot of time going to National Trust properties with my family over the years so it seemed a great opportunity to pay back.'

He says he was surprised at the size of the ship when he first entered the Longshed and enjoyed learning to work on planking the hull under instruction from the assistant shipwright Laurie Walker, and the team of volunteers.

‘It’s important that these techniques are kept alive,’ he says. ‘If these people weren’t here doing this, the boat would never be built and no one would see the techniques or be able to work out how things were done. We’re still learning about how the Anglo-Saxons built these boats.’

Apprentice Matthew Lee

Matthew Lee, 25, was working as a tree surgeon in South Yorkshire and was looking for something new when he chanced upon the National Trust apprenticeship scheme. He was delighted to be able to come to the Longshed in Woodbridge because he had been following the Ship’s Company project since it began. He also knows people who are working on similar reconstruction projects in Scandinavia.

‘They’ve worked on a few more boats there, so they’ve got more experience,’ he says. ‘But those are Viking ships and this is Saxon – the building techniques are completely different.

‘I like history and restoring things for the next generation,’ he says. He has a passion for what was created in the past with the tools and techniques available. ‘If you look at some of what they built, with the technology they had, to create cathedrals and stuff – it’s incredible.’

Matthew has had experience of working with axes in the past, both in felling trees and in other heritage work, although it’s not something he would use in his apprenticeship. ‘This is quite different to what we normally do. But I’m interested in experimental archaeology, and I’ve worked on heritage lottery projects like at Hatfield Moors, when we built a Neolithic house.’

All of the apprentices are guaranteed a year’s work with the National Trust after qualifying and Matthew hopes to stay within the heritage sector.

Apprentice Josh Bobbett

Josh Bobbett, 32, is used to working on Palladian style, Georgian buildings for his work with the National Trust in the Shropshire area. He had previously worked as a German teacher and repairing musical instruments among various jobs before being told about the National Trust apprenticeship scheme by a friend. Now he feels he’s found his passion.

‘I like to see the result of my work at the end of the day,’ he says. ‘With woodworking you can change something, you can make something. There are not a lot of jobs like that.’

For this project with the Ship’s Company, he’s using ancient methods and materials. ‘I haven’t seen a chisel in weeks,’ he says. ‘It’s experimental archaeology, using medieval equipment. It’s amazing how the Ship’s Company is hoping to go from spotting the trees they want to use for the timber to putting the ship on the sea at the end of it.

‘And I have a new appreciation of the material. When there was a knot in the tree, it added hours as you had to work around it. I’m used to having an industrial planer and if there is a knot or a twist in the timber, we can get it out.’

In his usual work restoring buildings, Josh says he enjoys being part of a bigger story. ‘I love it when you’re working on something and you take the paint off, say, and you can see that somebody else's hands have been working on it. How many people have there been between me and that other person?’